Post qualification admissions (PQA) is a simple idea, based on a simple premise: students should only receive offers from universities once they know their A-Level or equivalent results.

However, for around two decades admissions reform was something that everyone agreed was very important but little was done in the way of action. It would be, to put it simply, a massive administrative and communications undertaking.

Despite a very slow burn, whispers of revolution in dark corners of Westminster have become louder. Much louder. In fact, such is the current wave of popular opinion for introducing some form of PQA system, the government and sector bodies alike appear to be in a race to let everyone know that they wanted it before anyone else. This article discusses the motivation for change, and what a future PQA system might look like.

The current system

So why now? While the arguments that the current admissions system is broken have not changed much over the last few years, they have become harder to ignore. The DfE consultation launched in January cites three areas that have motivated the need for reform:

- The inaccuracy of predicted grades: UCAS’ 2019 end of cycle report noted that 79% of grades for accepted applicants who took at least 3 A Levels were overpredicted, while 8% were underpredicted. Ultimately this is having a significant impact on students’ decision making. One in four applicants surveyed by the Sutton Trust in 2020, said they would have made a different decision around university and course, if their decision had been based on their final grades.

- Simplicity and transparency: The current application process could be described at best, complex, and at worse, off-putting. Students are generally unsure how universities take into account work experience, volunteering and a respectful consideration of disadvantaged circumstances in their admissions. Equally there is a worrying discrepancy between published entry requirements and actual grades accepted. In 2019 around half (49%) of applicants who took at least 3 A Levels were accepted on to a course with lower grades than advertised.

- Unconditional offers: The poster-boy of admissions reform is certainly unconditional offers. While only 1.1% of 18-year-old applicants in England, Wales and Northern Ireland were given unconditional offers in 2013, by 2019 this had risen to 37.7%. As has been widely publicised, unconditional offers have been said to be responsible for unexpectedly poor A Level grades, and students accepting offers that may be suboptimal for them (as they don’t want to risk taking a conditional offer, and then not achieving the needed entry requirements).

Underpinning these three reasons is a need to change an admissions system that is currently negatively impacting on disadvantaged students. High achieving disadvantaged students are more likely to be under-predicted than high achieving non-disadvantaged students. As such fewer disadvantaged students apply for the most prestigious universities. The most disadvantaged students are also more likely to receive an offer with an unconditional component. Given that these students may be the first ones in their family to attend university, and have less exposure to the admissions system, there is a thought that they will be more risk averse. This could result in accepting an unconditional offer, and passing on another institution or course that would better match their expected grades.

To sum up, there is a feeling that the process is not as fair as it should be. In a recent survey from the Sutton Trust, two-thirds (66%) of students felt that applying after receiving final grades would be a fairer than the current system. The question turns then to what system could be better than the one we have now?

Two and a half models

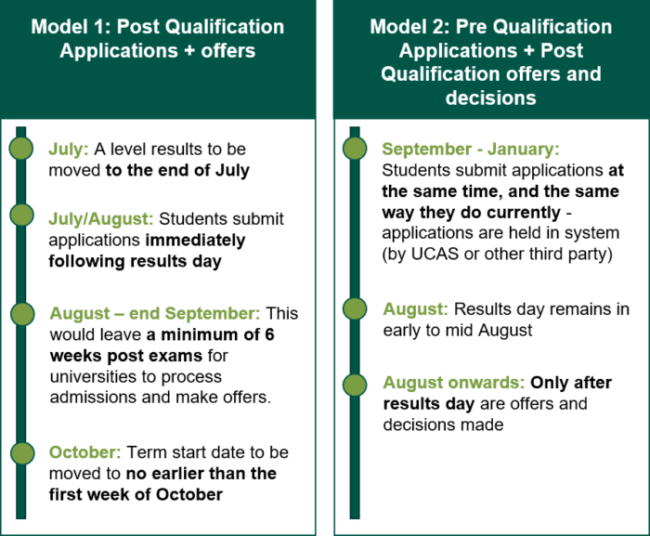

The DfE consultation put forward two PQA models for comment, which UCAS has since reflected on in their April ‘Reimagining UK Admissions’ report. The basis of the two models are shown below. UCAS’ recommendation essentially aligns with model 2, but also allows for multiple application points before results day. This enables students to change their mind regarding courses or institutions throughout Year 13, or to replace them following an unsuccessful interview.

Essentially, the crux of the issue is whether to adopt a gung-ho, full turbo PQA model, where applications, offers and decisions take place after exams (model 1), or a PQA lite approach, that involves pre-qualifications applications, and post-qualifications offers and decisions (model 2).

There are a number of issues to consider in a PQA lite approach, such as ensuring students successfully engage with universities to inform their decision making, the treatment and inclusion of international students, and how schools will adequately support students in decision making during the summer period.

At the moment however, it seems current sector thinking is that while these issues are surmountable, those inherent in a model 1 type PQA approach are not. In their report, UCAS argue that the changes to the timing of the academic year would be too large a pill to swallow for the following reasons:

- Lack of student support: The model would result in a five-to-six-month gap between taking exams and progressing to university or college with little support or maintenance, impacting disadvantaged students in particular.

- Competitive disadvantage: The model would move us out of sync with the rest of the world, causing UK HEIs to be less competitive globally.

- Added complexity: The model would result in compressing the whole admissions process into a few summer months. This would reduce teacher support during exploratory phases, and lead to some students making choices at the same time as others are conducting interviews or accepting offers.

Not only are these convincing arguments, but the fact that they come from UCAS may give us some indication of the future of PQA. UCAS currently plays a fundamental role in ensuring a consistent UK-wide approach to admissions, and it is very likely their role will remain central to adopting any PQA approach in the future.

A word of caution

It should be noted that despite the renewed optimism in PQA from the government and across the sector, it is not without its critics. For example, no PQA model inherently addresses issues of institution transparency when accepting or declining student applications. Furthermore, others doubt whether a PQA approach would actually do much to positively impact disadvantaged students. In the Higher Education Policy Institute’s (HEPI) recent report, Dr Mark Corver argues that “the belief that use of predicted grades harms equality is not supported by the data…and overall they may be more of an aid than a hindrance”. Much further discussion is required before a structured and well-evidence reform can take place. One thing is for sure though, after a long time in the background, PQA is now here to stay.