Any kind of transition in education can be stressful; the move from GCSE to A Level can be a momentous leap and moving on from school to college or University can present many challenges for even the most ambitious student. The state of wellbeing of our young people in the UK has been widely reported in recent years, and The Government has the mental health and wellbeing of those in Higher Education (HE) high on its agenda. Most mental health disorders make an appearance before the age of 24(1), meaning time in HE is a critical timeframe.

We were commissioned by DfE to measure and explore the various policies, practices and support offered to students in HE. This research builds on exploratory research conducted in 2019, with a view to informing improved and more effective practices nationwide. In total we interviewed 179 providers via an online survey (77 Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), 59 Further Education Colleges (FECs) and 43 Private Providers (PPs)). We also conducted more in-depth qualitative interviews with 75 of these.

Unlocking wellness

Before looking into the specifics, our first question looked at whether providers had a mental health or wellbeing strategy at all. We found that 61% of all providers did, 26% were planning on it and only 3% had no plans to create one.

When we specifically looked at HEIs, we found that the proportion with a policy or strategy in place had increased by fourteen percentage points when compared with the 2019 survey (from 52% in 2019 to 66% in 2022). So far, so good. But we needed to explore how HEIs planned to develop these strategies. With numerous frameworks and charters available to them, which ones were they using and were they fit for purpose?

Providers reported that they viewed the Student Minds Mental Health Charter as the most current framework and that they valued the use of the student voice. Many were working towards charter assessment. UUK and Papyrus “Suicide Safer” Framework provided many with a much-needed starting point to consider suicide prevention and the clear prevention, intervention, postvention structure helped many think about areas they would not usually consider. Each charter/framework came with noted downsides, and while the AOC mental Health and Wellbeing Charter was praised for its use in starting the develop a policy, it is not seen as being detailed enough to be used to create a full and robust policy.

Support services and partnerships

DfE have shared their ‘three pillars approach’ to tackling and improving wellbeing in HEIs (2), and with 89% of HEIs providing psychological support and self-help, there’s evidence that the providers are trying to fulfil that. But many noted that limited NHS capacity versus the rise in need meant that meeting student needs is no mean feat. In our interviews, many HEIs felt that their services were either oversubscribed or only just meeting demand.

84% of providers had a partnership with local NHS services and 72% had partnered with a local authority. HEIs were most likely to work with organisations who facilitated NHS care pathways (59%).

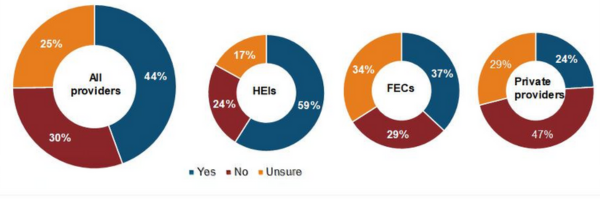

Figure 1: Whether external services involve facilitating NHS care pathways

D4: Do any of the external services you’ve mentioned involve these organisations facilitating NHS care pathways? Base: HEPs that use external services (169); HEIs (76); FECs (59); Private Providers (34).

Only 59% of providers were collecting data to monitor student mental health and 47% were collecting data on wellbeing. Of those, the most common types of information collected were about self-disclosed mental health issues, and support services accessed/required.

The road ahead

Our evidence shows that crucial work is being done and many providers are offering much-needed support. Services to support student mental health, wellbeing and suicide prevention are evolving and many HEPs in particular were reviewing their services and making changes to strengthen these, either through direct delivery or outsourcing.

None of our providers interviewed felt that student mental health and wellbeing is fully embedded throughout their institution. Further work is needed to embed these policies and ensure that students are better supported in their often stressful transition to adulthood. Some providers expressed a need for further funding in this area and noted the need for national guidance.

Earlier this year, it was announced that £15 million funding is being distributed to providers to support student mental health, including providing additional support for transitions from school or college to university, with a particular focus on providing counselling services for students. A target has been set for all universities to sign up to the Mental Health Charter Programme by September 2024.

In addition, Edward Peck is chairing the HE Mental Health Implementation Taskforce to set out a plan for further improvements in student mental health. The taskforce includes representatives from students, parents, mental health experts and the HE sector, and will deliver a final report by May 2024. (2).