In advance of next week’s Westminster Insight Graduate Employability Conference, we wanted to use the latest in our series of graduate outcome blogs to turn attention to a fascinating study that our Higher Education team conducted a few years ago for the Department for Education called ‘Planning for Success’.

Planning for Success

Although published in 2017, based on data gathered from graduates in 2015, the study remains very relevant today insofar as it highlighted the importance of the contextualisation of destination data. The research was designed to support a better understanding of how different graduates reach different outcomes.

Like Graduate Outcomes and DLHE before it, the research provided a snapshot of destination outcomes, in this case surveying the 2011/12 graduate cohort (7,500 UK domiciled full-time under-graduates from a large range of HEPs) and revisiting their responses to the 6-month DLHE survey two years later.

However, it also sought to better understand graduate ‘journeys’, exploring graduate expectations and ambitions, and their career planning and job search strategies. Most critically, we wanted to gain a better understanding of how different approaches impact on outcomes and what ultimately lies behind differences in employment rates and graduate outcomes.

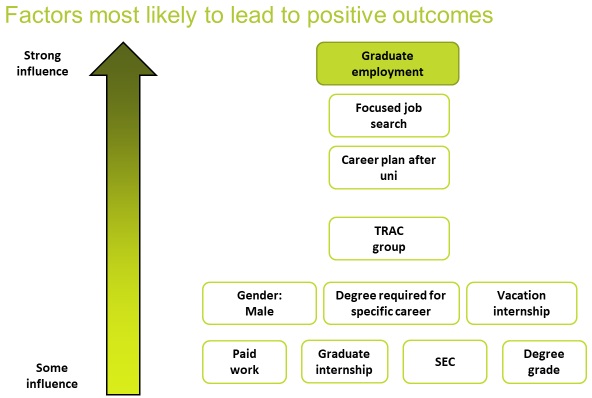

Factors most likely to lead to positive outcomes

There are a huge range of factors that can impact or influence graduate outcomes and the report goes into some detail on each of these. More complex, however, is understanding the relative importance or influence of these factors. To explore these relationships in more detail, we used multiple regression analysis. A statistical process compiling individual factors or “predictors” into a pot and ranking them in order of importance or influence in terms of their impact on outcomes.

These factors included:

- Demographics – SEC, gender, class of degree, type of university (TRAC group)

- Attitudinal – extent of career planning at different stages, reasons for going to university and undertaking course

- Behavioural:

- Work experience – whether undertook different types of work experience

- Use of university careers service

- CV building activities (volunteering, charity work, Student Union rep, representing university in a competitive capacity, receiving official awards for extracurricular activity)

- Job search strategies and approach to making applications (whether applying for jobs while at university or soon after / whether making applications only to grad roles while at university)

In total, 26 different specific factors or predictors were put into the regression model to assess the impact of these factors on a number of different outcomes. The chart below summarises the key determinants of graduate employment (as opposed to non-graduate employment) – for the stats behind this take a look at the report.

NB – this report also discusses a number of other models including any positive outcome vs unemployment as well as full time grad employment vs part time grad employment

Having a very targeted approach to job applications (i.e. those only applying to what they considered graduate level jobs, with most applications being made while at university) was found to be the most important factor in influencing whether a graduate ended up in managerial or professional employment as opposed to a non-graduate level job.

Second most influential was having a clear career plan – having a good idea about the types of jobs and careers upon completing university

TRAC group (a categorisation that groups institutions on % of income coming from research income and closely aligned with Tariff) was slightly less important although still played key role – those studying at Russell Group, medical schools and other institutions with a high proportion of income coming from research were more likely to end up in graduate employment, all else considered.

Around half as influential as TRAC group in determining graduate employment were:

- Gender – male more likely

- Having chosen to go to university mainly because a degree was needed to pursue a specific career (so even earlier signs of careers planning)

- Having done a vacation internship

In a nutshell, the study provided very clear statistical evidence of the critical importance of career planning in determining graduate outcomes, something that arguably gets forgotten when often the focus is on equipping students with the right employability skills or on related discourse around employability strategies within HEPs.