At a glance

Having launched a suite of support for Non-Domestic Organisations (NDOs) to cope with rapid energy price increases, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) needed to conduct an independent evaluation to assess its implementation and impacts. IFF is leading a consortium including our partners at Technopolis Group and Cambridge Econometrics, bringing together expertise in large-scale data collection, contribution analysis and quasi-experimental analysis.

About the client

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) was formed in February 2023, taking on the energy portfolio from the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). Its responsibilities include ensuring the security of the UK’s energy supply, meeting Net Zero commitments, and improving energy efficiency.

Challenges and objectives

In 2022, a combination of factors led to a dramatic increase in energy prices. Non-Domestic Organisations (NDOs – businesses, charities, public sector organisations) are not subject to a consumer energy price cap and, as such, were directly exposed to the volatility of the energy market. The Government introduced a suite of support schemes to shield non-domestic organisations from the worst of the energy crisis. This was a significant scheme in terms of financial investment, and the Department needed to commission a process and impact evaluation to assess whether the scheme was effective in its delivery, and had the desired impacts. There were several challenges associated with the evaluation, including the scale of data collection required, and the ability to isolate the impact of the schemes in an environment where all NDOs were eligible, and where a range of other schemes are operating to support businesses beyond the energy sphere.

Solution

The requirement called for a mixed methods approach, both in terms of data collection and analytical framework. IFF are leading the evaluation, with a large-scale programme of qualitative and quantitative data collection across a range of audiences sitting at its centre. However, the overarching evaluation design called for expertise in both Contribution Analysis (CA) and Quasi-Experimental Methods (QEM). We therefore partnered with Technopolis Group and Cambridge Econometrics who would lead on each of these respectively. We have worked with both organisations in the past, including successful delivery for DESNZ. Partnering with Technopolis and Cambridge meant that we could provide the Department with all of the expertise they required in one team, led by IFF Research.

“The waved approach to programme delivery, and the associated evaluations, places a strong focus on delivery learnings that can be taken forward in future schemes. We’ve been delighted to see how the evaluation findings have impacted and enhanced subsequent SHDF wave design, ensuring that social housing landlords and their residents can fully leverage the funding available. ”

Andrew Skone James, Director,

IFF Research

Impact

The evaluation identified key enablers and evidence of successful design and delivery including:

- Alignment of the Wave 1 scheme with social housing landlords’ decarbonisation plans, supporting the acceleration of delivery and improving quality of measures.

- Refinements to the Change Control Process from the previous Demonstrator scheme enabled quicker decisions and better project oversight.

- The mandatory PAS 2035 standards (which set out best practice for energy retrofit in existing homes) helped to ensure high quality installations.

- Localised projects enabled bulk savings in materials, logistics and labour.

Further to this, evidence from both social housing landlords and residents identified a number of key positive outcomes following the installation of energy saving measures:

- Energy efficiency improvements considerably reduced the reported number of problems in homes post-installation.

- Over four in ten residents with completed installations reported that they had reduced their gas or electricity use.

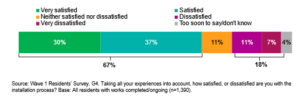

- As seen in the infographic below, two thirds (67%) of residents reported they were satisfied with the overall installation process.

However, the evaluation also identified some aspects of the design that negatively impacted the process. These included:

- Several social housing landlords felt that the application process requirements were onerous and, given the short bid timescales, that the process favoured more experienced or larger applicants.

- Project monitoring was a burden for some social housing landlords, who considered it disproportionate to the size of funding.

Additionally, Wave 1 experienced considerable delays to delivery, with the following contributing factors:

- Labour shortages in the retrofit industry, particularly installers trained in PAS 2035 standards.

- Unanticipated rising costs due to above expected inflation levels, affecting both labour and materials.

- A broader lack of knowledge regarding retrofit standards and accreditation requirements, among social housing landlords and those involved in the installation process.

- Residents refusing to give access to their properties.

Despite challenges with delivery, this research showed that Wave 1 of SHDF was of value to both social housing landlords, who would have otherwise delivered retrofit at a smaller scale and possibly lower quality, and to residents, who were generally satisfied with the installation of measures and reported improvements to issues previously experienced in their home. Learnings from the process have already been taken forward, with – for example – the Wave 3 scheme adapting the application process to make it more suitable for smaller social housing landlords.